Will the kids be alright? The conundrum of allowing children to play rugby league

It’s late Saturday morning when I arrive at Coomera Sports Park, a vast and sprawling sports hub in Gold Coast’s north. It’s an impressive site that you can easily get lost in, which I ultimately did.

On one field, you’ll find junior rugby union being played; on another Australian Rules football, and on the field far from where I parked my car, junior rugby league is being played. The home of the Coomera Cutters.

As I make my way through the car park, I spot a young boy and his dad practising last-minute tackling drills. The boy’s dad tells him, “Remember: you just want to ease into the game. For the first few sets you may be nervous, but don’t worry”.

As I get closer, I can hear the familiar cheers and claps of enthusiastic parents, along with the referee’s screeching whistle.

Not much has changed since I last played junior rugby. It’s the same bustling place, filled with excitable children racing around and hitting each other with their headgear. Mums can be seen carrying the half time oranges and drinking their coffee, while the dads mingle amongst each other talking about everything from work to last night’s NRL game.

What has changed since I last played is the existence of the Coomera Cutters, a team with perhaps the least imaginative name in the competition. The ‘Coomera Cavaliers’ sounds much better. I wonder if anyone else here is bemused by its name too.

The pitch at Coomera Sports Park is just like any other junior league venue. There is a canteen serving hot chips and dagwood dogs (the scent of hot oil still present in my mind), a mobile coffee cart where parents line up for their dose of caffeine, and of course, there are toilets which are too small to cater for the people here. Annoyingly, there are also no seats. I’ve resorted to sitting on the cement to type this.

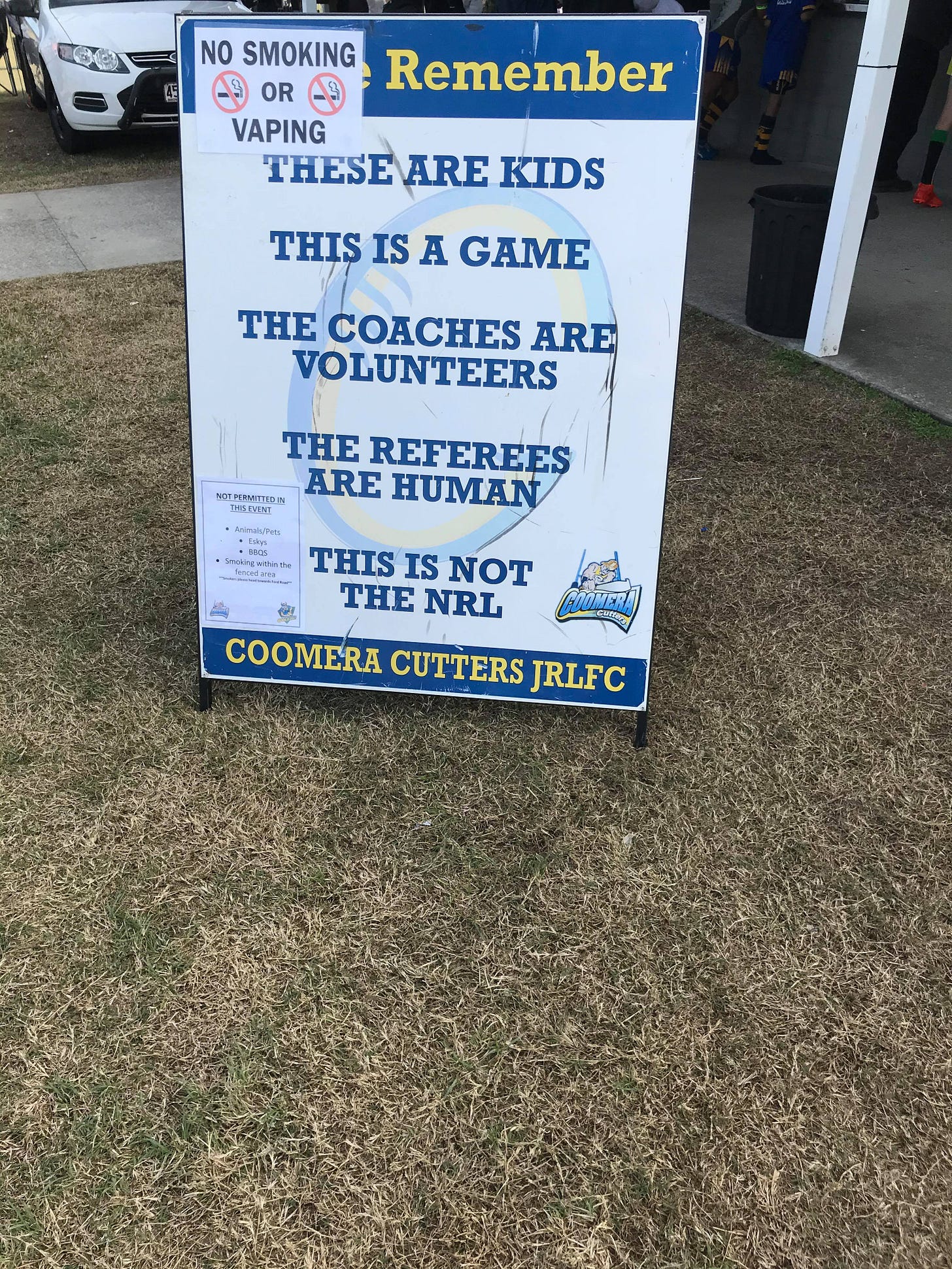

At the canteen, there is a sign catered towards parents. It reads: Please Remember - These are kids; This is a game; The coaches are volunteers; The referees are human; This is not the NRL.

It reminds me why I’m here: to figure out whether these children should be playing rugby league today.

It’s a very existential time for rugby league. This season, those watching the NRL will have noticed a dramatic rise in the amount of player suspensions, sin-bins and penalties – all a result of a “crackdown” by the NRL to decrease the potential for concussions and head injuries in the sport.

These crackdowns, or rules, include removing head-high contact from the game by harshly penalising players for dangerous conduct, and mandatory head injury assessments for injured players.

It has also been met with a sense of existential dread from traditionalists who believe the rules - or perhaps the public’s awareness of the game’s brutality - will end the sport for good.

The NRL’s reformative efforts have been propelled by recent developments about CTE, otherwise known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a neurodegenerative brain disease caused by repeated head trauma. Those who suffer from CTE exhibit symptoms such as memory loss, impulsive and violent behaviour, depression, and in some cases, suicide.

The only way to diagnose the disease is postmortem.

The emergence of CTE into the public consciousness came in the early noughties as the NFL grappled with its inherent brutality. American football, a sport famous for chaotic and explosive contact, did have consequences for those who played which would follow them into retirement.

Heightened awareness about CTE in the public, caused by a laundry list of player suicides, produced hysteria within the NFL, who internally went through the five stages of grief.

First, the NFL denied the existence of the disease and funded research to disprove its existence. When this wasn’t possible, bargaining occurred in the form of concussion protocols for players to follow.

Then came the anger from American football traditionalists. ‘This is going to ruin football!’ or even worse, ‘This is going to end football!’.

The anger eventually subsided and morphed into depression and acceptance when the sport’s dangerous and life-shortening nature was acknowledged by the NFL. It was indeed a very existential time.

It was time for the NRL to do some soul searching now.

However, despite all the noise surrounding head trauma in the senior game, little attention has been given to the junior side of rugby league.

With the link between CTE and contact sports confirmed, why are children still playing? Should children be playing? And what are the NRL doing to ensure the safety of children playing the game?

A sharp decline in the number of children playing rugby league is causing the NRL to worry about its future. The declining participation rate, a consequence of concerns about child safety, is making the NRL rethink how they deliver junior rugby league.

Dr. Wayne Usher, a sport health academic, had been tasked by the NRL to examine why their participation rates were declining.

Was Australian Rugby League Chairman, Peter V’landys’ right? Are potential juniors too busy on their “video machines” to play rugby league? Or is the sport too dangerous to play?

I interviewed Dr. Usher to discuss the decline of junior rugby league in the wider context of discussions about head trauma in the NRL. Dr. Usher found that the declining participation ratees correlated with heightened fears surrounding player safety and fear of injury.

“One of the things that did come through that complemented the drop was that parents were fearful about injuries,” explained Dr. Usher, “the main thing that made them move away from joining and continuing to play rugby league was that they were fearful of injuries”.

These concerns mainly stem from the vast weight differences of players in junior rugby league.

“That was a major concern that you have very large, heavy kids who are 15 years old that might weigh a hundred kilograms playing with kids that are half their size, so parents were quite alarmed about this type of thing” said Dr. Usher.

To prevent a mass exodus of junior players, the NRL has developed a plan to shift its traditional contact offerings towards a child-centric delivery of the game. These reforms include a weight-related division, a touch football program; and TackleSafe – a program designed to improve a child’s confidence and competence in tackling.

“Across the globe we’re seeing a shift from adult-driven sport to child-friendly centred delivery, so this has been found in every type of sport from ice hockey to rugby league,” explains Dr. Usher, “we’ve got to understand the difference between catering towards children and catering towards adults”.

The reforms were led by parents who increasingly became more aware about the risks of their child playing contact rugby league.

There have been more broad reforms enacted in the other code of rugby. Rugby Australia recently mandated that their junior contact rugby be segmented into weight divisions instead of age. These reforms have recently occurred in junior rugby union after concerns for player safety.

However, this shift has not occurred in junior rugby league. Not at Coomera Sports Park anyway. In fact, I am contemplating whether there is a weight division competition on the Gold Coast at all. In 2019, the NSWRL announced reforms to shift their divisions to weight, perhaps Queensland hasn’t yet caught on.

Specific to concussions, the NRL has also developed a ‘Return to Play’ policy which lists the requirements its junior players need to meet if they are to return to competition. These protocols include a 24 to 48-hour rest period, and a consultation with a doctor to clear their return. Upon return to action, children are eased back in with non-contact training before rejoining contact training before games.

And what do statistics say? Oddly enough, not much at all.

Not a lot of research has been conducted into the dangers of concussions in junior rugby league. In my research, I came across an Australian study which offered little help. The study stated that the percentage of injuries reported as concussions in junior rugby league were 2.2 to 24.6%. What?

The cynic in me is questioning whether statistics have been deliberately obscured to hide a more sinister fact, but maybe not. More conclusive research came from over the pond in Great Britain where research concluded that over the course of the season, the probability of a child or adolescent suffering a concussion was a staggering 22.7%.

I wonder how many parents are aware of that figure.

But if there was an existential threat looming over Coomera Sports Park, you wouldn’t have realised it. Many parents were cheerful and supportive, with little observable anxiety from spectators.

The atmosphere at the pitch felt communal and encouraging, rather than ravenous and raving. There was the odd applause for a good tackle, but it never felt like their children were in danger.

Though maybe that’s the problem as well.

One parent I spoke to did have concerns about the weight discrepancies.

“Yeah, that’s one thing [larger children playing] that I do worry about. My kid’s only small so it is something that does concern me. I’m surprised they haven’t sorted it out yet.”

What is troubling about concussions is that a person does not need to be knocked out to be concussed. The symptoms of a concussion may not even present themselves until the days following the collision. Subtle symptoms include being unable to sleep, mood swings, learning or memory difficulties and sensitivity to light and noise.

Though, the hard truth is that contact sports like rugby league always carries the potential risk for children to suffer concussions and other head injuries, such is the nature of the game.

And what can parents do if they do not wish to take their kids out of the traditional offering of contact rugby league? They could buy their child headgear, but sadly, headgear is more cosmetic than it is effective in limiting the impacts of concussions.

In fact, Sports Medicine Australia only recommends that headgear be worn to prevent lacerations and abrasions to the head only.

That doesn’t stop parents from buying it though.

In a phone call to Madison Sport, the leading provider of sporting protective equipment in Australia, I was told headgear sales had been surging this year.

“We’re actually having a bumper year for headgear,” said the friendly operator on the other end. I asked which headgear was most popular; was it the most expensive type?

“Actually, kids just pick their favourite colour rather than a particular type of headgear.” replied the operator.

Maybe even the kids know it’s more cosmetic than it is protective.

Watching the Cutters play, I’m reminded of my time playing rugby league. I’ve tried to suppress those memories, but unfortunately, it’s all come spilling out.

Nothing much terrible happened, but I’d rather save myself the embarrassment of remembering my feeble attempts at playing, if you could even call it that.

I remember my team the Ormeau Shearers doing battle against the ‘Mighty’ Nerang Roosters and some of the boys were as ‘mighty’ as the club nickname suggested.

They were a fearsome bunch, and I was happy to find myself sitting on the bench, hoping I wouldn’t be called upon.

Eventually my coach called upon me and I ran onto the main field at Brien Harris oval, the home of the Roosters to a large crowd of parents and onlookers.

I always remember this ground being more packed than any other I played at.

I was up. I lined up to take my first run and my dummy half obliged. In a state of horror and paralysis I realised my mistake. In front of me was their biggest player.

‘What am I doing here?’, I must’ve thought.

But instead of admitting defeat and passing to a teammate, I blindly ran into the fray - straight into the chest of my opposition.

Boom.

I wish I could tell you it ended well, but it didn’t. Instead, I fell onto my back like a sack of potatoes and laid haplessly on the oval for someone to put me out of my misery.

Shortly after that experience my playing career ended. Apart from that incident, I don’t remember getting hurt on the field, but my personal story isn’t rare. It’s indeed very common.

This experience jarred with what was in front of me while I watched the Cutters. Perhaps I was expecting an injury before I got there, but by now nobody had been injured, let alone visibly hurt.

To further jog back my memory I speak to my former Shearers teammate, Kirk, now aged 24. Having played junior rugby league for eleven years, Kirk’s playing days were cut short after injuring his knee during a game.

With my memories of junior rugby being shot (or repressed) I asked him if injuries were present during our time playing.

“Yeah, of course” said Kirk, “Not all the time, but it definitely happened.”

“Even concussions?” I probed.

“One hundred percent, I remember Braden [a teammate] getting concussions from playing. He had to stop playing because of it.”

As well as the injuries suffered, Kirk also made note of the competitive atmosphere present at some junior games.

“It was so competitive when we got older. I remember a team had just scored a try against us and the boys were going mad. I tried to calm things down and remind everyone that it was only a bit of fun and a teammate turned to me and said, ‘If you think this is just some fun then you shouldn’t be playing’”.

That toxic side of competition made itself present at Coomera Sports Park, particularly as the older age groups ran onto the field. This came to a head when the Cutters under-fifteens played my old side, the Ormeau Shearers.

The runs were hard and the tackles even harder.

Unlike games I had watched earlier, this game had an air of animosity to it. At times, it felt like a crude imitation of an NRL game, rather than an inconsequential game of junior rugby league.

After two halves of gruelling play, the whistle sounds to signal the end of their game and thankfully nobody is hurt.

In fact, throughout my day watching nobody had been hurt. Was that just luck? I expected to see a player injured, but nobody was.

At the end of each game, as per custom in junior rugby league, the players shake hands and leave their animosity on the field. The parents clap as their boys leave the pitch exhausted and ready to head home and back to school for the coming week.

Though nobody got hurt this weekend, who knows what will happen when these boys next make their way onto the field. Maybe this was one teenager’s lucky day.

I doubt they, nor their parents are thinking that far ahead. It’s probably the last thing on mum’s mind right now.